This article is mainly for newbies, but also for

those just interested in basic trad archery tackle criteria and

selection. The focus is on barebow archery as used for traditional

bowhunting, with longbows and recurves. The best thing a budding archer/bowhunter can do is to seek help from a qualified

mentor or coach who is well versed in the traditional side of archery

and bowhunting. One-on-one assistance will insure acquiring the right

tackle, the right setting of your gear, and learning fundamental *traditional* archery form

as it applies to hunting. Doing so can save enormous amounts of time

and money. Seek out help via local archery clubs, archery events, and

traditional archery shops.

In a hurry? Here are the key important points ...

1. Identify your dominant eye.

2. Seek a knowledgeable traditional archer/bowhunter to help with your gear selection, setup and learning how to shoot.

3. Traditional bowhunting starts with having consistent accuracy at realistic hunting distances, utilizing razor sharp cut-on-contact broadheads.

4. Read all of the text below.

5. Have fun!

The very first thing to learn is which of your eyes is the dominant one

- the one eye that focuses directly and clearly on an object. Hold a

hand about a foot in front of your face, make the "OK" sign circle by

touching thumb and forefinger, use both eyes to center a distant object

within that circle, close your left eye - if the object is still within

the circle, you're right eye dominant; vice versa if the left eye

centers the object. If you're right handed and right eye dominant, or

left handed and left eye dominant, no problem. Generally, right eye

dominant people should enter shooting sports as right-handed

participants. Left eye dominant people should participate as lefties.

Exceptions can be made to this general rule, but most of these

exceptions have to do with physical adversities.

PREAMBLE

If you are a budding new trad archer/bowhunter, you

will undoubtedly have many things to learn. Covered below are all the

gear/tackle basics. There is much more. However, it is strongly

suggested to avoid anything that will only complicate your learning

curve. Stick to the items listed below and do try to seek local

one-on-one personal assistance with choosing a stick bow, finding the

right arrows for your bow, and learning proper archery form.

SAFETY

Bows and arrows are lethal weapons. Even minisucle

light draw weight kid's bows can launch tiny arrows that have the

potential to kill humans, let alone critters. Use common sense. Here's

a link to a good LIST of archery safety concerns. Please read it.

THE BOW

We should all strive to employ a trad hunting stick

bow that has a holding draw weight we can manage. That is, a

comfortable holding weight that allows for consistency, which leads to

accuracy, which leads to accurate shots and quickly killed game. This is

a cornerstone of trad bowhunting, and there are no exceptions. Minimum

bow draw weight will be dictated by the bowhunting laws in the area(s)

you'll hunt, and the type of game you will hunt. However, you may

quickly find that a hunting weight stick bow for medium game such as

deer or hogs is too much to control, and if so, a much lower weight

starter bow will absolutely be required. You simply can not learn the

basics of good archery form if the bow has too much holding weight that

can't be controlled. Please read that again - this is very important!

Longbow or recurve? Doesn't matter. Pick one that makes you happiest.

What is the difference between a recurve and a

longbow? Here's the general consensus - if only the bowstring loops

touch the limb nocks, it's a longbow - anything else is a recurve.

Recurves are very efficient stick bows that

typically promote faster arrow speeds than longbows. Well then, why

bother with longbows, isn't faster better? Not at all necessarily,

because speed alone doesn't kill - consistent accurately placed sticks

with very sharp points do.

There are essentially two types of longbows - straight and hybrid.

"Straight" longbows have limbs that are basically

straight or perhaps with a bit of overall tapered reflex ("back set") or

string follow ("belly set"). These are "classic" longbows that form a

"D" shape when braced. Think: English longbow (ELB), American flat

longbow (AFL), Howard Hill longbow.

"Hybrid" longbows have both reflexed limb ends and

deflexed risers. This improves the overall efficiency of the bow, for

faster arrow speeds, while still imparting a large measure of bow

"stability" during the shot. Mild r/d hybrid longbows typically have that "D" braced classic longbow limb look when braced. Aggressive r/d hybrid longbows

will typically show some reflex near the limb tips when braced, and

allow even faster arrow speeds. The milder r/d longbows are typically

somewhat more stable than the more aggressive variety (aggressive

hybrids are closer in performance and aesthetics to recurves - and some

will outperform recurves in the speed category).

Stick bows have a number of measured qualities,

such as "stability" during and after the shot, "energy/speed" imparted

to the arrow via the limbs, "noise" created during the shot, and "hand

shock" after the arrow clears the riser.

Stability - the ability of the bow to remain as neutral as possible in the bow hand after the string is released.

Energy/speed - how much energy is imparted to the arrow as transmitted via the bowstring and bow limbs.

Noise - the decibel noise level after the string is

released and as the arrow clears the riser; recurves typically have

limb "slap", since the bowstring makes contact with the reflexed ends of

the limbs, longbows don't have that issue.

Hand shock - any amount of energy that is not

transmitted to the arrow is absorbed by the bow limbs and riser, and is

transmitted to the bow hand.

No matter what type of stick bow you choose,

be very careful choosing the holding weight!

be very careful choosing the holding weight!

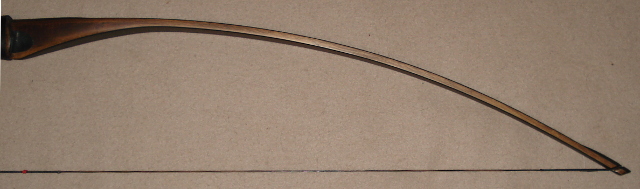

Bow limb images, braced and unbraced.

American Flat Longbow ("Howard Hill style") ...

Hybrid mild r/d longbow ...

Hybrid aggressive r/d longbow ...

Recurve ...

Bow Length. A proper length hunting stick

bow for a specific archer is dependent on some basic criteria - your

draw length, the type of stick bow, and perhaps special bowyer design

parameters. In almost all instances, longer stick bows will be more

stable, forgiving and easier to shoot. Longer may not be the best

choice if hunting from tree stands or blinds. Choose wisely!

Here are some guidelines for typical recurve bows ...

RECURVE

| |

| Bow Length | Draw Length |

58" | 24" to 27"

|

60" | 25" to 28"

|

62" | 26" to 29"

|

64" | 27" to 30"

|

66" | 28" to 33"

|

As you've already learned, longbows are typically divided into three types - here are some guidelines for typical "straight" AFL's (American Flat Longbows - i.e. "Howard Hill") ...

AFL LONGBOW

| |

| Bow Length | Draw Length |

64" | 26" to 27"

|

66" | 27" to 28"

|

68" | 28" to 29"

|

70" | 29" to 30"

|

... and here are some guidelines for typical "hybrid mild r/d" longbows ...

MILD R/D LONGBOW

| |

| Bow Length | Draw Length |

60" | 26" to 27"

|

62" | 27" to 28"

|

64" | 28" to 29"

|

66" | 29" to 30"

|

68" | 30" to 31"

|

... and finally, some guidelines for typical "hybrid aggressive r/d" longbows ...

AGGRESSIVE R/D LONGBOW

| |

Bow Length | Draw Length

|

56" | 26" to 28"

|

58" | 27" to 29"

|

60" | 28" to 29"

|

62" | 29" to 30"

|

64" | 30" to 31"

|

Please Note: There are

other, special design short length stick bows that will allow for much

longer draw lengths than shown above! Some stick bow lengths safely

allow for slightly longer draw lengths but may not be as smooth on the

draw as if used with a longer bow length.

As an example of an extreme hybrid aggressive r/d longbow, below is the 54" length TimberGhost TD

that was used by Curt Cabrera to win the coveted Overall Champion at

the grueling 2013 Muzzy Shoot ... Curt has a 29" draw length!

Bow holding weight is based on your draw

length. For a newbie, trad bow draw length can be tricky if not elusive.

Changing your draw length changes the bow holding weight! Know your

trad bow draw length! Seek one-on-one help from local, knowledgeable

folks - there is no substitute for this! Try before you buy is always

best, but not something one can do all the time (and one reason why

there's a good turnover of used stick bows for sale). You NEED a *reasonably*

light holding weight for your first bow, perhaps only 35 to 45 pounds

for a man, and 25 to 35 pounds for a woman. This will make learning

correct form much easier. If this first bow is a three piece take down,

getting a new set of heavier limbs will be less expensive than buying

an entire new stick bow. If you wish to hunt with your first trad bow,

it will need to meet the minimum legal holding weight/cast requirements

for your hunt venue location. To shoot well, and/or to hunt, or both?

Again, if you are not in control of your bow's holding weight at your

draw length, you are "over bowed" and you will compromise your archery

shooting/hunting.

Be realistic and wise when it comes to selecting your trad bow's holding weight!

Draw length is technically the distance

between the arrow's nock groove and the forward most inside of the

handle grip, then add an additional 1-3/4". If at full draw this

distance measures 26-1/4", adding 1-3/4" yields a 28" draw length. This

is a cumbersome way of determining an archer's draw length. Let's make

it easier and just as accurate. Your draw is measured from the depth of the arrow's nock to the front of the bow's arrow shelf.

You can check draw length with a long arrow or dowel (that has a notch

in one end to simulate the arrow nock) - mark the arrow/dowel in 1/2"

increments from the nock's notch, starting at 25" and ending at 30".

place a clothespin at the 25" mark, place the arrow/dowel on the

bowstring and draw back - the clothespin will move forward and will stop

when you reach your draw length. Note the distance. Add 1/2" or more

to this distance for your real hunting arrow's length (to allow for a

broadhead). Take note that as a trad newbie, your form will change, and

most likely so will your draw length!

Stick bows are marked with a holding weight, i.e. - 43# @ 28" (or typically labelled 43@28)

- this means the bow will hold at 43# when pulled back 28". For each

inch of draw more or less, add or subtract 3#. Be aware that the

labeled weights on bows may be off by as much as +/- 1 to 5 pounds - or

more! The ONLY way to know what weight you are holding at FULL DRAW

is to use a GOOD and TESTED bow scale. Anything else is a crap shoot!

REPEAT: If you start off with more holding

weight than your untrained muscles can handle, you will be weight

lifting and not shooting archery. "Overbowing" (attempting to use a bow

that is more draw weight than you can effectively handle) is a quick

way to poor accuracy, learning bad form habits that will plague you a

long time if not forever, disappointment, frustration, and maybe even

physical hurt.

If you are a compound archer starting off in trad archery,

be aware of two important things - (1) your draw length may shorten,

particularly if you're going from a release aid to fingers, and (2) the

holding weight of a compound can be between 10% and 90% of the

compound's rated weight at your draw length and you must take that into

serious consideration! If your current compound is rated at 65#, you

could easily be holding less than 15# at full draw, and if that is the

case you may have difficulty holding even a 45# stick bow at anchor!

You should be able to hold your stick bow at full draw for at least a

few seconds without serious shaking! Try before you buy!

As discussed above, bow length should be based on

your draw length and the design of the bow. There are some special,

really short length bows that are designed for longer draw lengths, if a

short bow is a requirement. For the most part, there are bowyer

recommendations for bow length. If you're up in the air (a tree stand)

or dealing with lots of thick bush (ground blind or stalking), shorter

might just be better for you. In the long run, there is at least a fair

amount of subjectivity to bow length. When in doubt, always go longer.

A one piece or take down bow? The real

consideration for a take down bow is travel, and air travel in

particular. T/D bows just make the bow hauling much easier for flying

out to a hunting venue. However, the cost of a take down can be

considerably more than a one piece.

Take down two piece or three piece? Geez, more

stuff to consider! There might typically be more inherent mass weight

with a three piece, and they have their own aesthetic "look",

particularly with a three piece longbow. Most two piece bows really do

look like one piece once they're connected - a much more pleasing

aesthetic look, but a tad more weight than a one piece, yet less weight

than a three piece. Some folks like the added mass weight of a T/D bow,

others like 'em lighter. More subjective stuff.

What trad bow? The quick, good answer is one of

recent manufacture. Older stick bows from the 50's to 70's (and some

even up to the 90's) can have issues, as can any used bow. Most of

these older bows will not be safe with modern HMPE bowstring fiber. For

the first time trad archer/bowhunter, avoid self, board and composite

wood bows - they require more care than a composite wood/glass stick

bow. Confused? That can be understandable. Seek knowledgeable help.

Trad archery clubs are best, as well as online advice from trad forums

such as TradGang.com

OK, you've got yourself a nice WhizBang stick bow,

it feels comfortable to draw, you can hold it at full draw for a few

seconds without shaking (well, not shaking too much - a little is fine

and something you should be able to correct as your muscles become

conditioned) ....

Now, learn how to shoot. Again, seek local

assistance, or better yet an archery coach, and one that is well versed

in traditional archery - there is no substitute for this as well.

Whether you employ split finger, or a three fingers under the nock

string grip, that's your subjective choice. Shooting a stick bow

essentially means nocking an arrow, gripping the string/arrow, drawing

the arrow to your draw length, holding at full draw (this "holding" can

be for a split second, or seconds), aiming at the target (or game),

releasing the arrow and "following through". What was not included in

the previous sentence is "stance" - how your body aligns with the

target. Target archers have the luxury of a fixed stance, which is

typically both feet in line with the target. Bowhunters learn to shoot

accurately from many body positions, from standing, to kneeling, to

sitting, to lying down. You MUST learn and acquire consistent accuracy

at reasonable hunting distances, and shooting in positions other than

the "target archery stance". For most trad bowhunters, this means

hitting a 9" paper plate at 15 yards, at the least.

The String Grip - how the string hand addresses the string. There are two recognized styles: "split finger" = pointer finger above the arrow nock and middle and ring fingers under the arrow nock (also called "Mediterranean style"), and "3 fingers under" = which is exactly as says, all three fingers under the arrow nock. With split finger, the most amount of string pressure is on the mmiddle and ring fingers ... for 3 fingers under, the most amount of string pressure is on the pointer and middle fingers. 3 fingers under has become very poplar as it allows the arrow to be closer to the aiming eye, and it allows "string walking" where the string is gripped anywhere between under the string nock point to inches below that string nock point. This allows using the arrow point for "point on" aiming at all target distances. Most newbie archers typically are taught the 3 fingers under method of string grip as it usually is easier for learning aiming, at least at short distances.

Aiming an archery bow means using some form

of sighting, and there are three basic types - hard sight, soft sight

and instinctive. "Hard sight" means using a moveable sighting device

attached directly to the bow. This is fine for target archery and known

target distances but nearly useless for traditional bowhunting with

unknown target distances. "Soft sight" means any aiming methodology

that employs aligning some part of the arrow or bow as a reference to

the target. Using the arrow point as distance reference to the target

(gap aiming) or placing the arrow point on a fixed object (point of aim)

are two soft sight aiming methods. "Instinctive" means looking only at

the target and disregarding both the arrow and the bow - this is

analogous to throwing a baseball or football or dart. This is by far

the most used aiming method for traditional bowhunters.

"Subjective Choice" - this can only best be

based on experience. Do not "think" something is "best" for you - go

out and try it, if at all possible. This subjectivity applies to both

archery tackle and shooting form/style.

FINGER PROTECTION

Pulling back a bowstring, even one on a light draw

weight bow, will hurt your string drawing fingers sooner than later.

The principle form of finger protection is a leather glove or tab.

Subjectivity rules here - try both styles of finger protection and

employ the one that feels best to you. Typically, gloves will have less

"string feel" imparted to the fingers, particularly if the glove is a

made from thick and/or stiff leather. Thinner gloves made with very

supple leather have really good string feel, and typically sport a much

higher price tag. Even a cheap leather tab will typically have good

string feel, and perhaps a better perceived "connection" to the string.

Choose whatever feels and works best for you.

THE BOWSTRING

Modern stick bows are almost always crafted to use modern low stretch, low creep string fibers. The High Modulus PolyEthylene

(HMPE) fibers (Fast Flight, DynaFlight, 450+, etc) have fiber trade

names such as Dyneema, Vectran and Spectra. Older bows aren't built to

handle HMPE string fibers and should only use bowstrings made from

Dacron fiber. Make sure that the brace height of the bow falls within

the range dictated by the bow's manufacturer. It doesn't matter at all

if the bowstring type is Flemish or endless.

It's more in a newbie's favor to use a modern stick

bow since that will allow the use of modern string fibers. As

mentioned, HMPE strings are more consistent and stable and that means

both better accuracy and less to blame on your equipment when accuracy

and form issues arise. Almost all older, vintage type bows are not safe

to use modern low stretch/creep string fibers - stick with Dacron

(polyester) for those older bows.

THE BOWSTRING NOCK POINT

Use a bowstring square or a sheet of folded

newspaper to find where the bow's arrow shelf lines up with the string

at 90 degrees. Roughly 3/8" to 3/4" above that is a decent starting

point for the arrow's nocking point (arrows nock under that nocking

point). Adjust the nocking point up or down until there is no up/down

("porpoising") of the arrow in flight as it leaves the bow. Use a metal

nock point for ease of adjusting purposes. Later on, replacing that

metal nock point with a tied-on and glued thread nock point will make

for a tad faster string, and one that's less likely to chew up your

shooting glove or tab.

THE ARROW

Of all archery tackle, the arrow is absolutely most important

- certainly far more important than the bow. Whatever your holding draw

weight, you want an arrow that will fly well out of your bow. Arrows

that don't fly straight and true are less efficient and less accurate

than ones that do fly well. Efficient arrows with sharp cut-on-contact

broadheads that fly true to the spot on an animal will kill that game

faster than any other type of arrow criteria. Read that again.

Matching an arrow to a given bow and archer is a

task not for this article. Arrow shaft materials are wood, aluminum,

fiberglass and carbon. It's recommended to at least initially stay away

from wood arrows - they will be too inconsistent, are affected by the

environment, and require constant attention to straightening - not to

mention they are just not as durable as man made material arrow

shafting. Use either aluminum or carbon arrows. Aluminum arrows will

be the easiest to tweak for matching to a given bow. However, carbon

shaft arrows are the most durable and consistent, and can be fairly easy

to match to a bow (see note below), and offer the greatest range of

weight and spine for any given shaft size. Yes, there are LOTS of folks

that would argue differently - but day in and day out, carbon shafting

has more than proved itself for bowhunting. An extremely important

aspect of carbon arrows is shot after shot consistency in terms of shaft

straightness - no other shaft can compare in that quality. This is a

very important factor for a newbie archer - the more consistent your

arrows and other tackle, the more you'll know where the blame goes when

you have accuracy issues. Note that whatever your draw length, the arrow

needs to be at least 1/2" longer, but can be 2" or more longer if need

be.

Note - when it comes to carbon arrow shafts, do not

rely on manufacturer's "spine charts". Carbon shafting is just

different than aluminum and wood, when it comes to stiffness ('spine')

and their static spine is quite different than their dynamic spine.

Going lower in carbon shaft spine is almost always better than the chart

recommendations. There's a reason why carbon shaft spine ratings are

very broad for any given carbon shaft (i.e. - 35#-55# spine rating for

one shaft type).

Getting an arrow to fly well out of a bow

begins with choosing a completed arrow that's as closely matched to both

the bow and archer as possible. Newbie archer/bowhunters should always

seek knowledgeable help in arrow selection. This is extremely

important. Attempting to excel in archery/bowhunting with less than

optimum flying arrows is a sure way to fail, or at least make your

journey unnecessarily hard - and expensive. Please read that again.

THE BROADHEAD

For traditional

bowhunting, choose a twin, triple or four blade cut-on-contact

broadhead. Lots of popular brands and models. If they're super sharp,

they'll kill well if you do your job. Lots of info abounds on broadhead

sharpening and attachment methods. Screw-in or glue-on? With carbon or

aluminium arrows, glue-on broadheads allow point weight adjusting by

using different point adapter weights, thus adjusting the overall point

weight, which allows tweaking the arrow's spine (stiffness), GPP (Grains

Per Pound - divide the arrow's weight in grains by the bow's holding

weight) and FOC (Front Of Center - the precise balance point of the

completed arrow).

SHARPENING BROADHEADS

Whether two or three blades, the results should be a razor sharp broadhead or knife that's capable of shaving hair.

THE FLETCHING

Above all, have fun!

Please feel free to email me for further assistance ... TG Admin

SHARPENING BROADHEADS

Once an archer can consistently make accurate arrow

shot placements at realistic hunting distances, the payload delivered

must be a razor sharp cut-on-contact broadhead. Arrows lethally kill

critters via blood loss. A really sharp broadhead arrow in a critter's

vitals promotes maximum bleeding and a quick, ethically humane animal

death. Getting a broadhead *sharp* means raising a burr on the blade

edges, then very lightly removing that burr to reveal the razor's

shaving edge. At the very least, to do this properly (raise the burr)

requires a good mill bastard file, setting a good blade angle, and some

practice. Much can be found on the web about hand sharpening broadheads

and knives, including the "How To - Resources" forum at www.TradGang.com.

There are a number of sharpening tools that can

take the blade angle setting guesswork out of the sharpening equation. A

highly recommended twin blade (and four blade) sharpening tool is the KME Knife Sharpener,

which will sharpen both twin and four blade broadheads with the same

precision it will sharpen knives. Really sharp knives are another

requirement for dressing out your kill, so the KME affords double duty

for one price tag.

Tri blade broadheads are best sharpened on a 12"

flat mill bastard file. Lie the head flat down on the file, with the

point of the head facing the handle of the file, and push. Be

aggressive, particularly if the blades are not dead straight - make them

straight. To hasten this process, a 120 grit sanding station or belt

sander can be used to both flatten the blades and lightly remove the

needle point found on most 3 blade broadheads - lift up the rear of the

head and slightly "pyramid" the tip. Whether sander or file, rotate the

blades to make uniform passes. When your fingers can feel the burr

forming, make a few more passes. Then very lightly swirl off the burrs

with a fine oil stone or diamond stone - use no pressure, allow the

stone to do the work.

The most important tip for sharpening any type of

blade is this: 90% of sharpening anything is accomplished at the

coarsest stage, be that a file, belt sander or your coarsest stone. If

we don't get the blade sharp (and I mean VERY sharp) right at stage one,

then moving on to finer grits will only polish the bevels and it will

not get the blade any sharper. (translation - your coarsest file or

stone is your best friend).

Whether two or three blades, the results should be a razor sharp broadhead or knife that's capable of shaving hair.

THE FLETCHING

Feathered fletches say "traditional archery" and

are the easiest, most forgiving, and perhaps the most efficient to use.

The feather's "wing" (left or right), doesn't matter as long as the

feathers/fletches used for each arrow are of the same wing. For a

hunting arrow that pushes a broadhead, a large 5" fletch is recommended,

aligned with as much offset or helical as possible, in either 3 or 4

fletch configuration. How they're stuck on (glue or tape), is also just

personal subjective stuff as all will work one way or another.

Practice does make perfect. Roving is great

practice for bowhunting. Use judo points and take shots at varied

objects (tree stumps, bushes, cow pies, grass clumps) at varied

distances and angles. The only game better than roving is BOW HUNTING!

Above all, have fun!

Please feel free to email me for further assistance ... TG Admin